This past week I had to write a short paper on Lectio Divina, an ancient method of reading scripture, and so I thought I would share it here. I not only had to write about it but I have to select ten scriptures to practice this method with, I shared the ten passages I picked and invite you to participate with me in the coming weeks. (Note: This is a non-technical research paper.)

------------------------------------

Throughout

history in Christianity, Lectio Divina

(Latin for “divine reading”) has been a traditional practice of scriptural

reading. It is specifically used by Benedictine monks and followers under the

Benedictine tradition. The practice is intended to promote communion with God and

to increase the knowledge OF God's Word, rather than just knowledge ABOUT God’s

Word. The practice consists of reading the text with as little lenses on as

possible. It does not treat Scripture as texts to be studied, but as the Living

Word, pieces of communication from God that should touch the very soul of each

person.

The

roots of Scriptural reflection and interpretation go back to Origen in the 3rd

century, after whom Ambrose the Bishop of Milan taught them to St. Augustine of

Hippo. The monastic practice of Lectio

Divina was first established in the 6th century by Saint Benedict and was

then formalized as a 4 step process by the Carthusian monk, Guigo II in the

12th century. In the 20th century, Pope Paul VI recommended the practice of Lectio Divina for the general public to

aid in spiritual formation. In recent years, Pope Benedict XVI emphasized the

importance of practicing this four step reading of the Scriptures for anyone

who took their Christian faith seriously. [1]

The

roots of Scriptural reflection and interpretation go back to Origen in the 3rd

century, after whom Ambrose the Bishop of Milan taught them to St. Augustine of

Hippo. The monastic practice of Lectio

Divina was first established in the 6th century by Saint Benedict and was

then formalized as a 4 step process by the Carthusian monk, Guigo II in the

12th century. In the 20th century, Pope Paul VI recommended the practice of Lectio Divina for the general public to

aid in spiritual formation. In recent years, Pope Benedict XVI emphasized the

importance of practicing this four step reading of the Scriptures for anyone

who took their Christian faith seriously. [1]

The

thesis of the Old Testament from Moses through the prophets to the people of Israel

can be summed up in one word: “Listen!” It comes up in a very poignant way in

the Great Shema: “Sh'ma Israel: Hear,

O Israel!” (Deuteronomy 6:4) In Lectio

Divina we are stilling ourselves to follow that command. We listen and turn

to the Scriptures. In order to hear someone speaking softly we must learn to be

silent. Lectio Divina teaches us to

love silence. This is the first step, reading, truly reading, senses attuned to

the voice of Christ. Traditionally Lectio

Divina has 4 separate steps: read, meditate, pray and contemplate. After a short

passage of Scripture is read aloud in a quiet place, some traditions suggest pausing

and then reading it aloud at least three times as its meaning is reflected

upon, thus following the practice of triune repetition. [2]

The monks believe thrice reciting the pericope is a way we invite the Trinity

into our reading.

The

art of Lectio Divina begins with

cultivating the ability to listen deeply, to hear “with the ear of our hearts”

as St. Benedict encourages us in the Prologue to the Rule of Faith. When we

read the Scriptures we should try to imitate Jesus who went away seeking a

quiet place to pray, we should follow the example of the prophet Elijah by

allowing ourselves to become people who listen for the still, small voice of

God (I Kings 19:12); the faint voice from within that it is sometimes called, which

under the tradition of Lectio Divina

is God's word for us. [3]

Many believe that through this practice of slowing and listening we feel and we

can hear God's voice touching our very hearts. This gentle listening is an

acknowledgment that God is present and speaking in the Scriptures in an

intimate way.

This

reading is followed by prayer and contemplation. Lectio Divina is broken into its four steps like so:

Lectio - Reading the Bible passage gently and slowly several

times. The passage itself is not as important as the savoring of each portion

of the reading, constantly listening for the "still, small voice" of

a word or phrase that somehow speaks to the practitioner.

Meditatio - Reflecting on the text of the passage and thinking about how it applies to one's own life. This is considered to be a very personal reading of the Scripture and very personal application.

Oratio – Responding to the passage by opening the heart to God. This is not primarily an intellectual exercise, but is thought to be more of the beginning of a conversation with God.

Contemplatio - Listening to God. This is a freeing of oneself from one's own thoughts, both mundane and holy, and hearing God talk to us. Opening the mind, heart, and soul to the influence of God. [4]

Meditatio - Reflecting on the text of the passage and thinking about how it applies to one's own life. This is considered to be a very personal reading of the Scripture and very personal application.

Oratio – Responding to the passage by opening the heart to God. This is not primarily an intellectual exercise, but is thought to be more of the beginning of a conversation with God.

Contemplatio - Listening to God. This is a freeing of oneself from one's own thoughts, both mundane and holy, and hearing God talk to us. Opening the mind, heart, and soul to the influence of God. [4]

While

the Lectio Divina has been the key

method of meditation and contemplation within the Benedictine, Cistercian and

Carthusian orders, other Christian religious orders (Protestantism,

Evangelicalism, Orthodoxy) have used other methods.

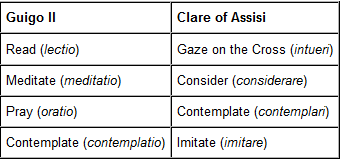

An

example is the 4 step approach of Saint Clare of Assisi (shown in the table)

which is used by the Franciscan order. Clare's method is more visual than Guigo

II's which seems more intellectual in comparison. [5]

Saint

Teresa of Avila's method of "recollection" which uses book passages

to keep focus during meditation has similarities to the way Lectio Divina uses a specific Scriptural

passage as the centerpiece of a session of meditation and contemplation. It is

likely that Teresa did not initially know of Guigo II's methods, although she

may have been indirectly influenced by those teachings via the works of

Francisco de Osuna which she studied in detail. [6]

Saint

Teresa of Avila's method of "recollection" which uses book passages

to keep focus during meditation has similarities to the way Lectio Divina uses a specific Scriptural

passage as the centerpiece of a session of meditation and contemplation. It is

likely that Teresa did not initially know of Guigo II's methods, although she

may have been indirectly influenced by those teachings via the works of

Francisco de Osuna which she studied in detail. [6]

The

focus of Lectio Divina is not a

theological analysis of biblical passages but a reflection. Often times monks

suggest reading the texts Christologically, not in the analysis sense, but seeking

Jesus in the pericope so that the reader may find the meaning God would have

them find in that moment. In essence, it is a way to commune with our maker by

allowing emotion and intuition to go uninhibited by the mind.

Many

times when practicing Lectio Divina we miss an important step: Prayer.

It is through prayer that we enter into contemplation. We are seeking God not

just in the text but also with our hearts and with our words. Prayer aligns our

hearts with Christ, and gives us eyes to see meaning where meaning may have

been hidden before. We are not spending time with just an ordinary book but

entering into a conversation.

Ten

Scriptures that come to mind as I practice this method of Scripture reading

could honestly be found completely in the Psalms, however neglecting the

narrative of the Old Testament, the doctrine of the Apostles in the letters, or

the life giving words of Jesus in the Gospels would not be beneficial to the

reader seeking to hear a full message from God. A step that I think is

overlooked and one that I would add to the process of Lectio Divina without any hesitation is: Selection. The Spirit must

lead in the selection of the scriptures to meditate on as much as He leads in

the reading of it, the meditation, prayer, and contemplation of the messages.

We understand that the Bible is the complete word of God, that the canon we

have has been prayed over, and prayed through, picked apart, scrutinized,

critically examined and yet has come to us in the same form as when it was

written and canonized. We understand that it is the full message of God and

cannot be changed or altered, but when we take a piece of Scripture and choose

our pericope to meditate upon we must not do so at the expense of others. And

so, for when we are seeking the voice of God in our quiet time, our devotions,

or in preparation for a sermon we have to ask and pray through the selection of

scripture Christ would have us take time to dwell on. One of my professors, Peter Buckland, likes to

say that when we have chosen a scripture to preach on, we must present it in

such a way that our listeners can chew on it, but only after we have chewed,

tasted, and savored it ourselves. Lectio

Divina is another way of practicing this art of dwelling on, or chewing and

savoring scripture. It is a way in which we pull Scripture into ourselves and

open our own spirit up to change and be conformed to the image of Christ.

And

so, this list is subject to change, but where I am at right now these are the

scriptures I would choose to divinely read:

Genesis 16:6-15

1 Samuel 30:1-6

2 Kings 6:8-17

Psalm 46

Psalm 63

Isaiah 30:15-21

Mark 4:26-29

Ephesians 3:14-21

Colossians 1:9-14

Revelation 3:14-22

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources:

The

Way of Perfection by Teresa of

Avila 2007 page 145

Christian

spirituality: themes from the tradition

by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 page 38

ACCEPTING THE EMBRACE of GOD: THE ANCIENT ART of

LECTIO DIVINA

by Father Luke Dysinger, O.S.B. 2001 http://www.valyermo.com/ld-art.html

(Peer Reviewed article by a Catholic Priest, I found it after it was cited in Studzinski’s book)

(Peer Reviewed article by a Catholic Priest, I found it after it was cited in Studzinski’s book)

Reading

to live: the evolving practice of Lectio divina

by Raymond Studzinski 2010 pages 26-35

***Pictures and

Charts as well as the explanation of the charts are directly from Wikipedia’s

page on Lectio Divina found here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lectio_Divina

(Surprisingly,

Wikipedia was the only place, other than the one book I cited above that I

could find the info on Guigo II that was in English and not Latin. Apparently

most of his writings have not been translated yet. Whether or not he actually

came up with the four pillars all on his own for sure, I do not know. It is

historically attributed to him though.)

Works Consulted (No direct

citations.)

After

Augustine: the meditative reader and the text

by Brian Stock 2001 page 105

Opening

to God: Lectio Divina and Life as Prayer

by David G. Benner 2010 pages 47-53

Guigo the

Carthusian, The Ladder of Monks and Twelve Meditations: A Letter on the

Contemplative Life, trans Edmund Colledge and James Walsh, (London:

Mowbray, 1978; reprinted Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1981) [This

was originally printed in the Sources Chretiennes series as Lettre sur la

vie contemplative. Douze meditations, ed Edmund Colledge and James Walsh,

SC 163]

[1]

Studzinski

[2]

Cunningham

[3]

Dysinger

[4]

Studzinski

[5]

Wikipedia

(See note above.)

[6]

Teresa

of Avila

-----

Nathan Bryant

Is a student of Ozark Christian College in Joplin, Missouri. Majoring in Biblical Leadership, New Testament Studies, and Missiology, he has a combined passion for unity and discipleship in the global church. Nate is a crazed sports fan, he enjoys college football and playing fantasy football. He also enjoys watching baseball with friends. He works as an Admissions Counselor and Resident Assistant at Ozark. Nate is unashamedly a Starbucks addict. Yay Coffee!

Christ's Kingdom is bigger than our causes.

No comments:

Post a Comment